|

Remembering Timothy Leary

Jon Carroll graciously lent me his column

to publish this eulogy in The San Francisco Chronicle on May 31, 1996.

I first met Timothy Leary when I was a producer

at Activision, trying to keep up with his

wildly complex ideas about a videogame based

on cinema and interpersonal psychology. On

my first trip down to LA to work with him

he met me at the airport, striding down the

concourse dressed in white pants, a white

sweater, white sneakers and white hair, and

whisked me off in an old pea-green Mercedes

with broken seat belts. (The second time

I came down I had to call him from the airport

for directions. "Get to the Beverly

Hilton," he said, "and then you

just come whirling and swirling up the hill.")

There were always dozens of people at Tim's

house - mostly young, sometimes famous, always

burning with energy and fiercely fond of

the old man. At the end of that first hard

day's work, Tim broke some brownies out of

the freezer. "Dr. Leary," I said,

"are those, uh, marijuana brownies?"

He looked at me in mock astonishment. "I'm

Timothy Leary," he explained.

But Timothy Leary didn't die of split chromosomes,

marijuana lungs, or incurable drug-induced

insanity. He died of an old man's disease,

just plain old prostate cancer. He also drank

too much alcohol and smoked too many cigarettes.

He went to West Point, did you know that?

- and built a patio on his house in Berkeley

in the 50s with his own hands, for the kids

to play on. Eerily standard American stuff.

From his book Flashbacks I learned about the amazing energy and dedication

with which he was persecuted by nearly every

level of law enforcement, finally landing

in solitary in Folsom prison for possession

of a roach. "As I walked toward the

cell," he told me, "I knew I had

a choice - I could either have a really bad

time or I could learn something. I started

learning."

|

|

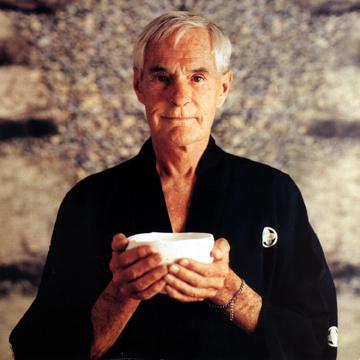

|---|---|

| Photo From Asahi Magazine, 10/25/89 |

America will have to ask itself what it was

about Dr. Tim that was so damned scary. He

was a Berkeley Ph.D. who was one of the founders

of interpersonal psychology, and a Harvard

professor who was completely absorbed with

studying the human brain and fell into research

involving psychedelics long before they were

illegal. His transgression, in Calvinist

America, may simply have been that he stumbled

onto an instant source of illumination and

joy. These things are supposed to cost you,

bigtime, and they are supposed to come from

the Big Guy in Heaven, not the resources

of your own mind under the influence of a

plant or a chemical compound or even a spiritual

discipline, unless it is devoted to a divine

Other from whom the gift of enlightenment

flows. Although he wasn't particularly anti-Christian

(he attended Sacred Heart - did you know

that?), Dr. Tim's fundamental humanism challenged

every sort of authority, from religion to

law.

During the late 80s and early 90s Timothy

and I often found ourselves speaking at the

same conferences, usually devoted to virtual

reality or technology and culture, in places

like Barcelona, Linz (he called it "Hitler's

home town"), and Normal, Illinois. It

was heart-warming to see how his basic message

affected the kids in his audience. He sat

on the edge of the stage at the college in

Normal and in his breathy, awestruck voice

revealed the great secret: "You are

the owner and operator of your own brain."

This wasn't about acid - it was about autonomy,

agency, and the great secret that we have

within us a deep source of personal power.

After his talk in Normal some of the students

invited him back to their apartment. It was

a perfect replica of a 60s pad, complete

with black light and Hendrix poster. They

addressed him reverently. Tiring of the sedate

conversation, Tim decided that everyone should

get rowdy and dance. We whirled and swirled

around the apartment to vintage Stones. The

kids loved it. Finally he asked somebody

to pour him a drink. After some embarrassed

scrambling in the kitchen, a fellow was dispatched

to the neighbor's for a shot of Bourbon -

there wasn't a drop of booze or a speck of

marijuana in the house.

The most important thing I learned from Timothy

was tolerance. He could find something to

appreciate in anybody. He listened to everyone

who talked to him. He never treated a fan

or a student like an inferior, nor did he

fawn on celebrities. He steadfastly refused

to judge people. "Liddy's okay,"

he said when I asked him how on earth he

could go on a world speaking tour with the

man who first established himself in "law

enforcement" with the Millbrook bust.

"Liddy's intense. Liddy's Liddy."

The last time I saw Tim he was luminous.

I could feel the heat pouring off his body

as he sat a foot away, but when he reached

over and took my hand his skin was cool and

dry. "Every day is a precious jewel,"

he whispered in that awesome-secret voice.

Leary's Leary. I love you, Tim.