|

When Interval Research was founded the original

24 members of the research staff were challenged

by David Liddle to "create something

as different from the personal computer as

it was from the mainframe".

When Interval Research was founded the original

24 members of the research staff were challenged

by David Liddle to "create something

as different from the personal computer as

it was from the mainframe".I thought about this, in a structural manner, and concluded that the right way to proceed was by systematically inverting a number of the media theoretic elements of what a personal computer (or work-station) was (circa 1993).

A work-station:

- Communicates to people via a two and a half dimensional grid of semantic relations (i.e., the desktop metaphor).

- Has a paucity of input senses - a keyboard and mouse.

- Is fixed in space - it sits on a desk.

- Constrains the body of the user to a cramped posture and limited set of gestures.

- There is one work-station per user.

- Communicate emotionally - facial expressions, affective sound, bodily gestures.

- Use multiple sensory modalities that are shared by humans - including vision, touch, and hearing.

- Make something that can move around independently.

- Have it move/experience/act through the same physical and social spaces as people do.

- Make lots of them - and have them exhibit flocking behavior.

I argued against simulation of such, because

people would inevitably react differently

to something on a screen as opposed to an

entity with a body in space. Therefore building

real physical robots was deemed essential

in order to create a joined system where

people were the environment for the robots,

and vice versa, and we could ask such questions

of people as what is the robot feeling?

I argued against simulation of such, because

people would inevitably react differently

to something on a screen as opposed to an

entity with a body in space. Therefore building

real physical robots was deemed essential

in order to create a joined system where

people were the environment for the robots,

and vice versa, and we could ask such questions

of people as what is the robot feeling?When the project was started, it was in uncharted territory - no one else was doing anything similar. The patent search for the background intellectual property uncovered only a few remotely relevant pieces of intellectual property - a flocking patent, a game patent, and a few others.

My grand strategic goal for the project was to do a strong design statement, that would produce design heuristics that others could emulate. Such a strong design statement could be subsequently relaxed from its initial purity of expression to find use in other areas, such as adding affective communication into workstations - in other words, one would not have to always make a full up robot to take advantage of the understandings produced by first building an emotionally communicating robot.

|

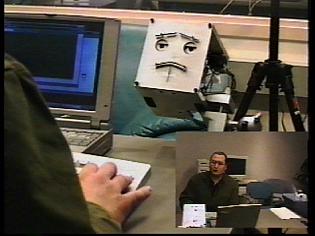

| John Pinto in the Aquarium lab controlling the Mark One "Severed Head" |

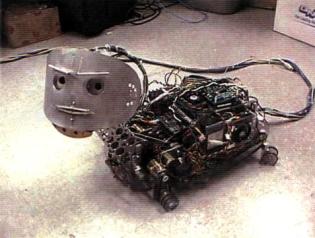

Then we proceeded to build a full up robot.

The end result, four years later, was a prototype

robot that had an expressive face, a mobile

body with a articulated neck and head; gestures

that emulated the ballistic motions of animal

gestures; a sense of touch that differentiated

between a caress, a light contact, and a

blow (using sub-modalities of an accelerometer

and a capacitive sensor); stereo color vision

that located peoples bodies in space and

tracked them via 3D blob analysis; had male

or female gendered emotionally expressive

audio - and implemented an internal emotional

state machine that emulated the seven basic

expressive emotions described by Charles

Darwin in in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and

Animals.

The end result, four years later, was a prototype

robot that had an expressive face, a mobile

body with a articulated neck and head; gestures

that emulated the ballistic motions of animal

gestures; a sense of touch that differentiated

between a caress, a light contact, and a

blow (using sub-modalities of an accelerometer

and a capacitive sensor); stereo color vision

that located peoples bodies in space and

tracked them via 3D blob analysis; had male

or female gendered emotionally expressive

audio - and implemented an internal emotional

state machine that emulated the seven basic

expressive emotions described by Charles

Darwin in in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and

Animals.  By 1998 others had started to work in the

same general area. Some of these poured far

more resources into their engineering - notably

Sony with the Aibo robotic dog. In the annual

project review I argued that we should either

spin the project out of Interval as a development

effort aimed at real products in the toy

market with enough resources to succeed,

or we should kill the project. In the end,

I killed my own dog - the project was ended.

By 1998 others had started to work in the

same general area. Some of these poured far

more resources into their engineering - notably

Sony with the Aibo robotic dog. In the annual

project review I argued that we should either

spin the project out of Interval as a development

effort aimed at real products in the toy

market with enough resources to succeed,

or we should kill the project. In the end,

I killed my own dog - the project was ended.Mark Scheeff, the member of the research staff who did the mechanical design for the robot, followed on with a six month "cremator project" He ripped all of the AI out of the system, and turned the robot into a tele-operated puppet, to explore what people perceived about the robot, not knowing what it was "under the hood" - i.e, what they projected onto the media surface. He exhibited it at the Tech Museum in San Jose, and members of the project under his leadership published a paper summarizing the results from this exploration of projective intelligence:

Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Robotics and Entertainment (WIRE-2000): Experiences with Sparky, a Social Robot, Mark Scheeff, John Pinto, Kris Rahardja, Scott Snibbe, Rob Tow .

The other tangible result from the project was a very broad patent (and a subsequent improvement patent with the same title) covering emotional communication between real robots with actual bodies with each other and with people:

- Tow, R. Affect-based Robot Communication Methods and Systems - U.S. Patent No 5,832,189, November, 1998.

- Tow, R. Affect-based Robot Communication Methods

and Systems - U.S. Patent No 6038493, March, 2000. This

was a continuation of the first robot patent

above, emphasizing claims related to actual

bodies in space as opposed to simulated bodies.